Every Single Memory #1: First Memories

Memories from a childhood in Virginia, and moments in Hong Kong and North Korea. From a new series exploring memory, emotion, and culture.

I am in the dark, no older than three.

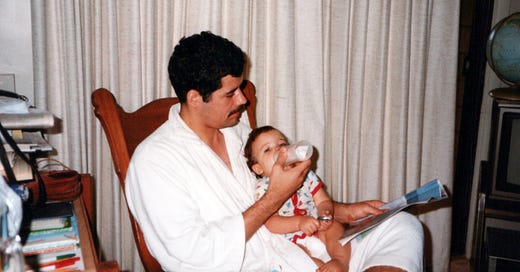

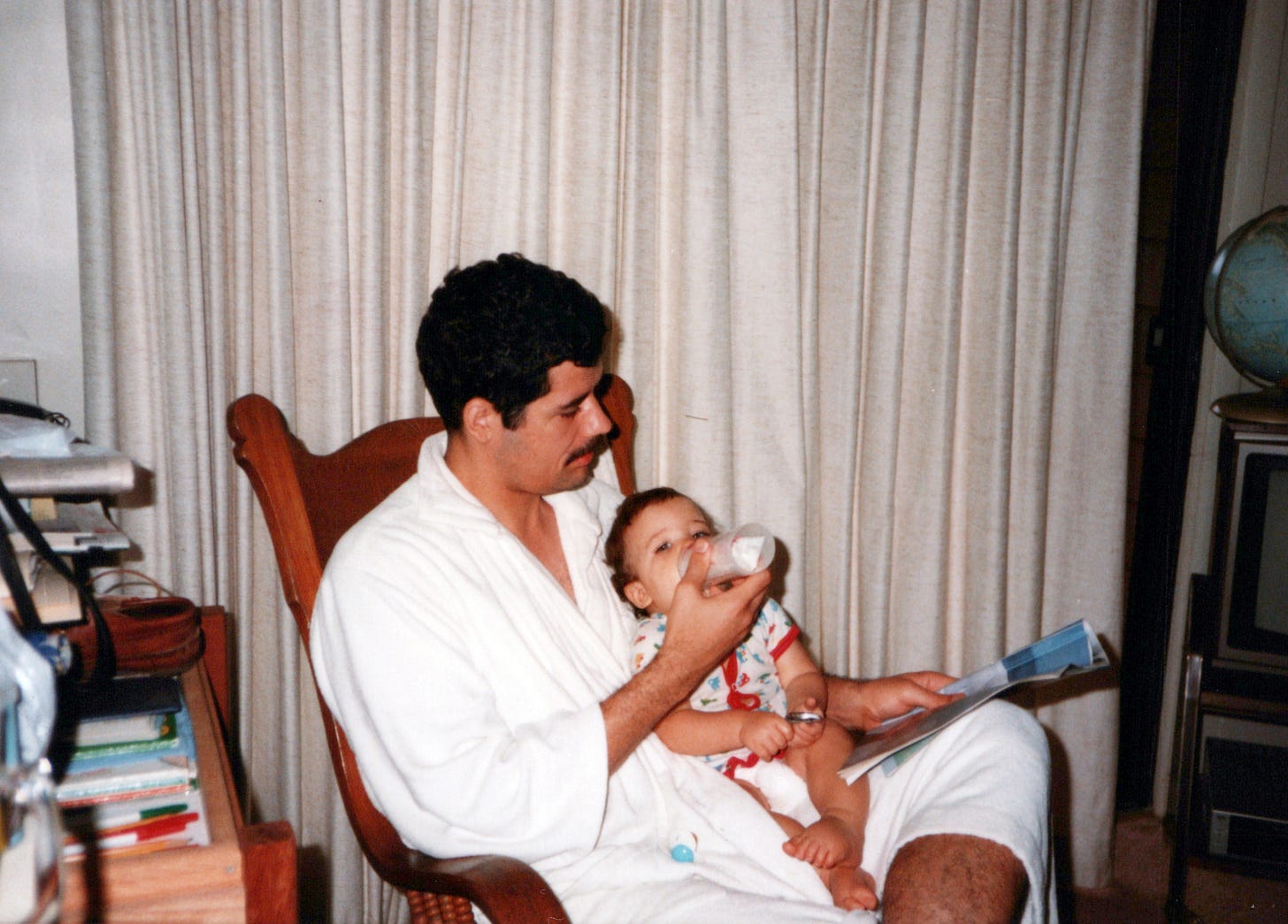

My father sleeps beside me in bed, but I am awake, terrified of the formless shape on the mirror across the room. It’s both static and changing. Something that you can’t stare at for long without feeling it was staring back at you.

This is my first memory.

I am small against my father, whose upper body alone is larger than I am. His legs seem to drift forever, like the tentacles of an enormous jellyfish in the depths of the ocean. But I know nothing of jellyfish, or the broader world around me. That analogy is an adult’s interpretation of a child’s memory. At that time, I live in the moment, unaware of just how unaware I am.

It is not until writing this that I realize it is possible that my own self, shrouded in shadows, was looking back.

Years later, in my early thirties, I go on a 10-day silent meditation retreat, at a meditation center in Australia, located above a river which has just flooded. I cry over two deaths which have not happened yet—my father’s and my own.

Recalling it, I begin to attribute meaning to my first memory. The darkness, the fear of my own reflection, being with my father, death.

More likely, I was just a kid afraid of the dark.

~

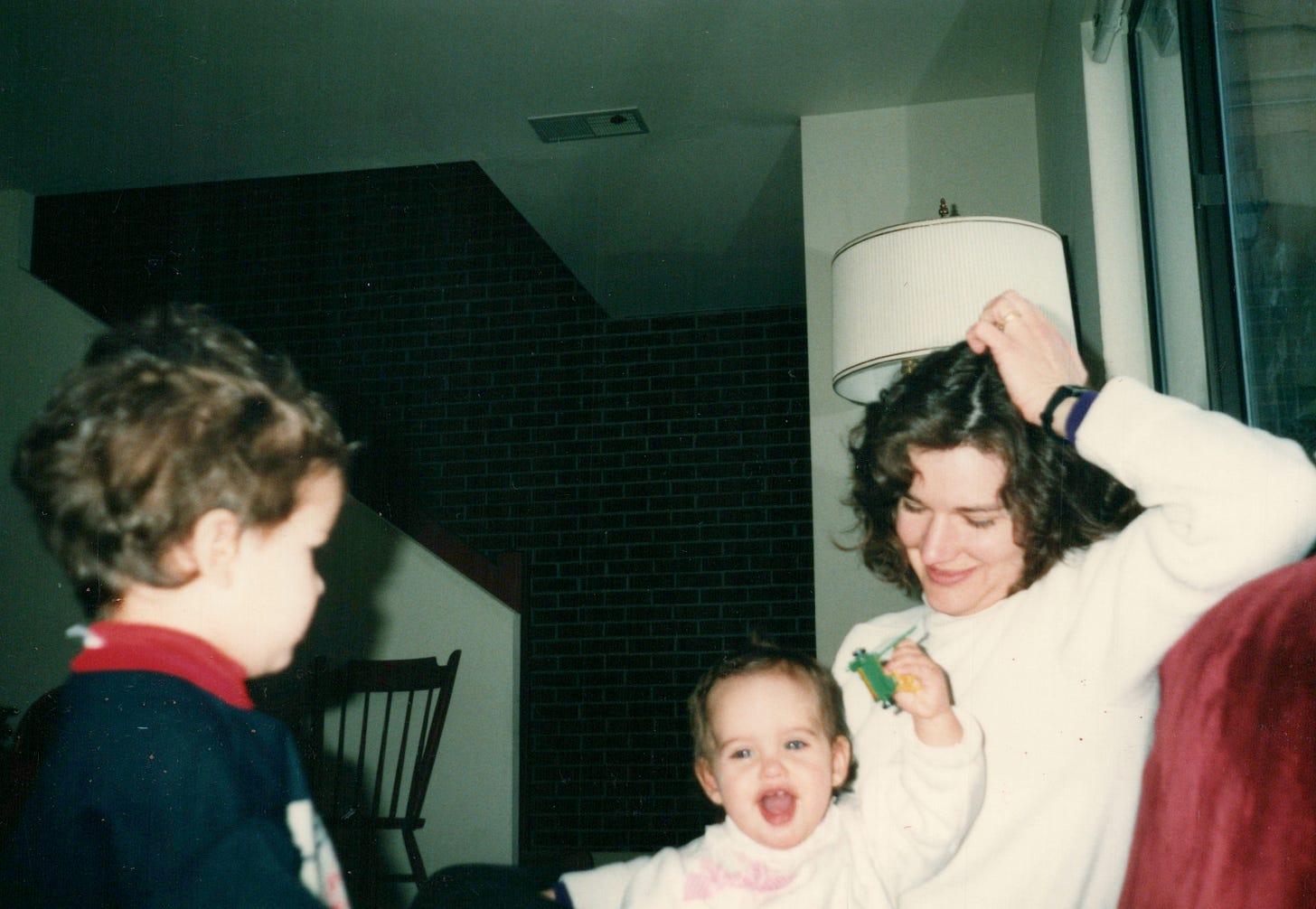

In my second memory, my grandmother is cooking. She towers over me, as does the oven, and the refrigerator across the room. I run into the kitchen, filled with cheap white cabinets and a vinyl floor.

This might be my only memory where I truly remember what it felt like to be a tiny kid. But I was not small—everything else was huge. I run to my grandma, my head near her knees, hidden by her long dress. I strain to reach up, wanting to be included.

She ignores me, and I try to feel what she is doing, because I cannot see. Lightly burning my hand, I shriek and cry and run to my mother in the other room.

~

I once saw my mother cry, reading a 50-year-old letter her father had written. He died when she was young, and she has no memories of him.

His absence to me was normal, but for her, it meant growing up without a father, an absence that probably stuck out when she visited her friend’s families, or watched movies where fathers appeared.

She did not have the luxury of crying about a future where her father would not be around.

~

As a child, the vastness of the world compared to my own diminutive size makes everything a game.

The stairs are like a mountain. My third memory, which weakens each time I remember it, is happy. My sister and I throw my father’s thin socks at the large brick wall. Some stick to the wall, and we laugh with joy.

It is a reminder that children can make a game out of anything.

It is also my final memory at the first house I lived in.

In 2013, I visit North Korea, and as we leave a village, two young children hide behind large rocks, then suddenly pop out, waving and yelling to us, before hiding again, then reappearing once more.

It occurs to me that these children have no concept of where they live, or that their life will soon dramatically change. They’re just kids, and like all kids, they like to play and eat and laugh. They don’t care about politics, or macroeconomics, or global rivalries. It doesn’t matter that I am American. They wave to me, and I wave back.

I realize how similar I was to them. Me, throwing socks against a brick wall with my sister, or them, hiding behind rocks and laughing, popping out and waving. Now, a decade has passed, and these kids are now teenagers. Culture and politics now separates us. As children, we were so similar, yet now our daily lives must be so different.

~

At what point does childlike innocence become ignorance?

With knowledge, understanding is certainly gained. But so too is something precious lost

As a child I blindly trust my parents, unaware of larger, more complicated realities. But I was lucky. They were kind to me, and I was happy.

~

Not everyone is lucky.

~

When I was about 10, I found photographs like these, of myself as a tiny child, laughing as my parents smiled. I sobbed, helpless at the passage of time. Even though I was 10, I felt impossibly distant from the child I used to be. Perhaps because of the fact I could faintly remember what it was like to be 3 or 4, I was acutely aware of just how much I had changed, and how clearly I was old now. Anxious, I ran out onto the deck of my childhood home, amidst trees covered in leaves of a bright summer’s green.

~

Now, I’m old enough where these photos bring more joy than sadness. Being further from those moments somehow makes seeing them more of a reminder of something I once loved, rather than a memory of something that was recently lost.

~

When I was 19 and lived in Hong Kong, I knew a woman with tattoos and piercings. She told me that she too had cried about her parent’s deaths, even though they hadn’t happened, had looked at photographs and sobbed at the passage of time. She was only 18, but felt older than me, such was her maturity and effortless cool. She got her first tattoo at sixteen, and though this made her feel so mature at the time, I now realize those tattoos were a sign of youth and impulsivity—perhaps even a teenage disregard for the future. Years later, before we lost contact, she told me she regretted them. But now I wonder if the same things which made her seem so old to me at the time will make her feel young when we are both elderly. She will carry those tattoos forever, and on her aged body will forever be a visible, but fading, reminder of being sixteen.

~

Around that time, I thought of getting a dragon tattoo, since my father and I were both born in the year of the dragon. But so many foreigners had dragon tattoos it no longer felt special.

I am not sure if adjusting my plans based on others is a way of preserving joy or ruining it.

~

This piece is part of a new series called 'Every Single Memory,' an attempt to catalog and link memory and experience across time and culture. In the future, we may open the series to submissions, creating a collective exploration of memory and meaning.

Thanks for reading Poetry Culture! If you’d like to support us, consider checking out our pencils, notebooks, shirts or other merchandise, available at poetryculture.com/shop or buying a subscription right here on Substack <3.

If you like what you read, I’d really appreciate your support via a voluntary subscription.

This is so beautiful. It was a pleasure to get lost in your memories, Alex!

Well done. Beautiful prose. Reminds me of a writing exercise I did a few days back. Take a photograph or recall when in your memory and start it off with “in this one you are… “

It seems simple, but it’s very effective…